No one had mentioned the state test until after Christmas. It arrived in our world like a warning siren in the fog—a letter home, a bulletin on the wall, the computer lab lady lingering longer in the hallway with a clipboard. It would be the first of its kind: a computerized assessment that determined whether you passed 8th grade or not.

The rules were simple, brutal. You had to demonstrate mastery of two tasks:

1. Open a spreadsheet, enter a formula, and save to disk.

2. Open a word processor, type a heading and a sentence, and save to disk.

If you failed either, you failed 8th grade. No curve. No makeup.

Sometime around March, someone realized we were behind. Other schools had been preparing since fall. We had two months. Weekly Mac lab sessions were mandated immediately.

The Mac lab wasn’t like the regular computer lab. The machines were newer, sleeker, with those cheerful beige towers and small color monitors that blinked awake like a robot's eye. You weren’t allowed to touch them until told. Each computer had a disk drive. Each student had a diskette—the flimsy plastic square that held your future.

We learned in slow motion. Double-clicking was a skill. The spreadsheet program opened into a blank field that looked like math and felt like drowning. The word processor was barely less alien. Type a heading. Type a sentence. Save. Eject. Label your diskette. Place it in the box.

Randy Freeman, known universally as Biggun, struggled most with fonts. He had large hands and a mild expression and a heart full of try. The text formatting menu made no sense to him. Each week he hovered over it, clicking hopelessly. Until one glorious day when, eyes wide with pride, he called to us:

"Look, look!"

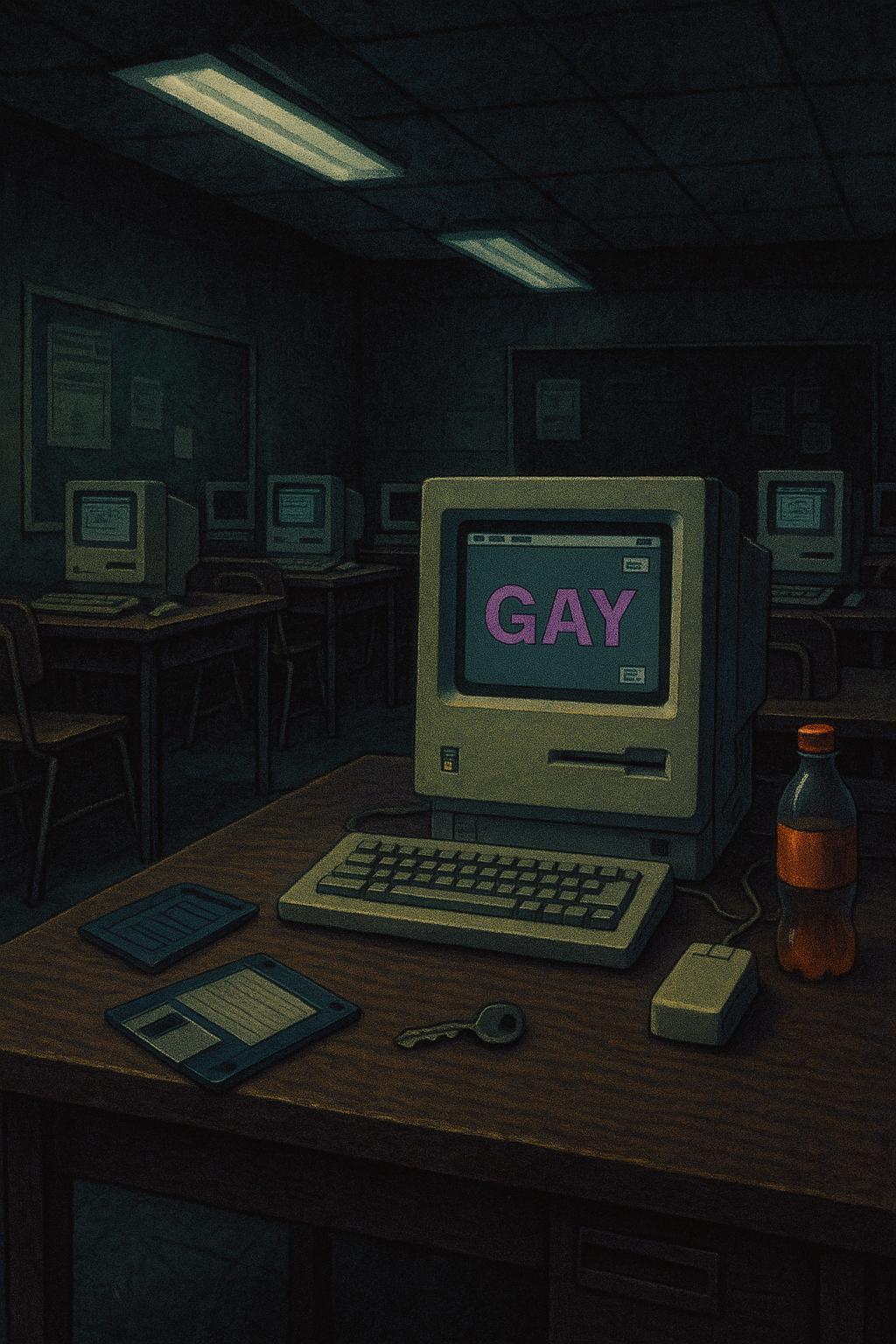

On the screen: a single word. GAY. Bold. Purple. 24-point.

No one laughed. We weren’t that kind of class. We just looked at Biggun, at the pride in his face, and nodded. He had done it. He had found the font.

As May approached, the pressure mounted. The lab took on a quiet intensity. We whispered less. We saved more often. We watched the screen like it might betray us. During our final practice session, the air felt tight. This was it. Our last rehearsal before the state test.

When the session ended, we lined up to return our diskettes. The diskette enclosure—a grey plastic box with slotted dividers—sat by the door. The lab lady stepped out to take a call. I was last in line.

I don’t know what came over me. Maybe it was panic. Maybe boredom. Maybe fate. My fingers moved without command. I flipped a few diskettes over, not reading the labels. I felt for the little tabs—the write protection switches—and clicked them into the locked position. Maybe five. Maybe six. I don’t know. My face was hot. My stomach turned. I caught up with the others, already nauseous from what I’d done.

Test day came like judgment. We filed in, each handed our own diskette. We were quiet, even Biggun. The instructions were read aloud by the lab lady like a court order. We began.

For a while, all was still.

Then a hand went up. Then another. Then two more. Panic murmured through the rows. The machines were displaying strange errors. Cannot write to disk. Disk is write-protected. Please insert writable disk.

Terrified fingers waved in the air. Some students cried. Others froze. The lab lady moved from desk to desk, peering down, frowning, squinting at the screens.

"Show me what you diyud," she muttered.

Then she stood still.

She looked at the error message on someone's screen. She looked at us. Then she turned and ran from the room. Not briskly. Not professionally. She ran, her orthopedic shoes squeaking.

We sat in stunned silence.

She had gone to call.... RALEIGH.

Like the State Guard might arrive in helicopters to restore educational order. Like someone would break down the door with a crowbar and fix the disk drives. Like the stakes had been real all along.

And maybe they were.

No one ever found out who did it.